Short Answer: A LOT.

Long Answer: Like a lot of things, it is a little bit different depending on the medium.

No matter what medium or budget level, I think it is really important to have clear vision for the shots that you want.

I’ll give you two different examples, one is working in TV Movies and the other is an independent feature film.

TV Movies

My first Director-for-Hire jobs were on television movies. These tend to be lower budget – particularly when you’re just starting out – and have a very limited number of shoot and prep days. And one person who usually has way fewer prep days that you do is the cinematographer.

During prep as a director you’ll be kept very busy with location scouting, casting, and meetings of all kinds – art department/set decoration, props, costumes, picture cars, background casting, scheduling, and on and on. Since your cinematographer only has a couple days of prep with one usually being the equipment load-in day and another being the tech survey you really need to be prepared for any conversations you do get to have with them before you’re both on set. A lot of times cinematographer might be willing to email/chat with you before they’re officially on the clock but that’s not a guarantee. For one thing, they could be working on another project up until shortly before their start date on yours. Here is what I do in a situation where I’m working mostly on my own before talking to a cinematographer:

I write out a somewhat general shot list based on the scenes as they’re written. When working in TV Movies there is an expected visual language that you need to keep within AND budget/time constraints – my TV movies have been 12 day shoots with basically no budgeted overtime for cast/crew. For a lot of scenes you will do pretty traditional coverage (Wide, Medium, Close) or some slight variation on it depending on how early in the show it is/how established a location is for the audience. You want to pick your moments to put your own visual stamp on the movie. Note down these ideas as they come to you. As you get closer to principal photography and you have a better idea of the schedule and locations you’ll know which ones of your super cool ideas are possible and which ones will eat up your day and compromise your other scenes. Having one A+ scene mixed in with a bunch of C+ scenes won’t make your movie better and can reflect really poorly on you as a director-for-hire.

I also really like to do what I’ve called a visual shot list. It’s sort of like a storyboard but instead of my terrible drawings, I collect stills from films and tv shows that I’m inspired by – I use Shot Deck but a broker version of me also used Google Image Search. One thing I’ve found working with everyone from cast to crew to producers is that we all use words slightly differently, so whenever you can SHOW someone what you mean, you’re much more likely to get what you’re looking for.

I send the written and the visual shot list to my cinematographer and then usually they’ll tell me the stuff they really like in it, ask questions about what specifically I want out of certain shots based on the images I’ve sent, or send some photos of their own to make sure we’re communicating well. This back and forth is really important as you’re building a relationship and a language that the two of you can communicate in when time is short and stress is high.

As you lock down your locations, you’ll be able to be more specific with your shot listing. I usually get time to go to locations by myself, or with my 1st AD to think through the shots. On location I usually try to think through them in shooting order based on the current schedule. It helps me foresee potential time sucks or other issues I can bring up with the team.

On some TV Movies I’ve been able to do a location walk through with my cinematographer in advance of the Tech Survey. I show them the different areas of the location that I like and what scenes I was planning on shooting where (maybe a scene is scripted for a dining room, but a house has a gorgeous kitchen and I’d rather shoot it there… or maybe that was the only scene in the dining room and it would take up A LOT of time to do that equipment shuffle). They will show me things they like about the location, different angles that I hadn’t thought of shooting from, or even really cool shots they’d like to get if possible.

And after all that preparation, you throw everything out the window and shoot! Well, not quite, but being thoroughly prepared allows you to respond creatively when a curveball is thrown your way. Preparation = Way Fewer Freakouts.

Independent Feature Film

A lot of similarities, but also a lot of differences. Generally, with a feature you’ll have more prep time, or at least more soft prep time (aka no one is on the clock yet, but you can still be preparing). I use my soft prep time to write down ideas for shots and seek out a lot of visual references. One of my favourite things I ever did in soft prep was with my cinematographer on my feature film What Comes Next. Over the course of a few days we got together and would read the script out loud one scene or sequence at a time. We’d discuss the scene, what it meant to me creatively, what the key idea was – the one thing I wanted to get across to the audience, and any ideas I already had for how I wanted to shoot it. We would also share visual references with each other and talk about movies or scenes the project reminded us of. What made this process so great for me was I knew there was at least one other person on set with me who deeply understood what I was trying to do in each scene, and it helped us build a strong, connected, working relationship. This was our first project together and many people on the crew thought we’d known each other for years.

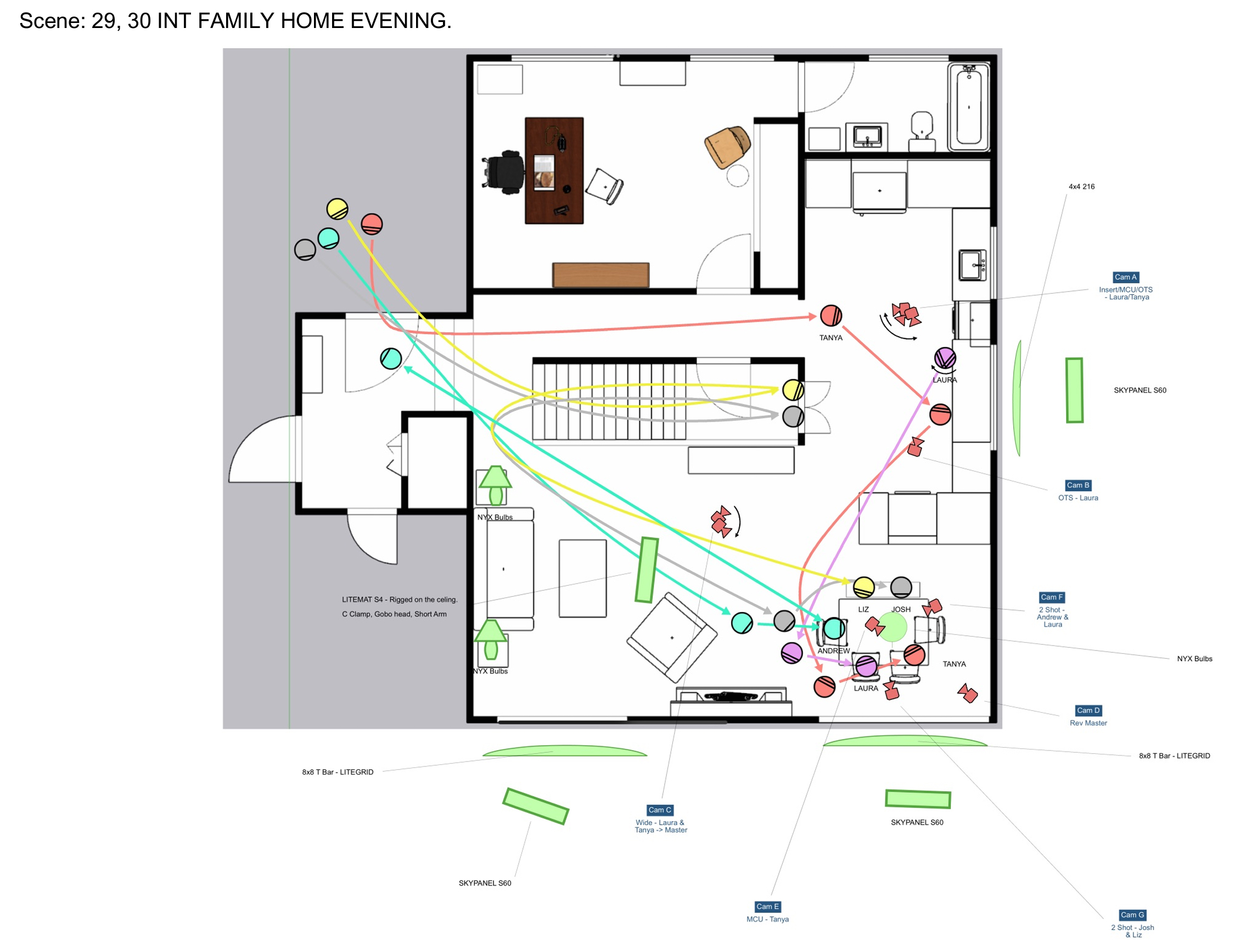

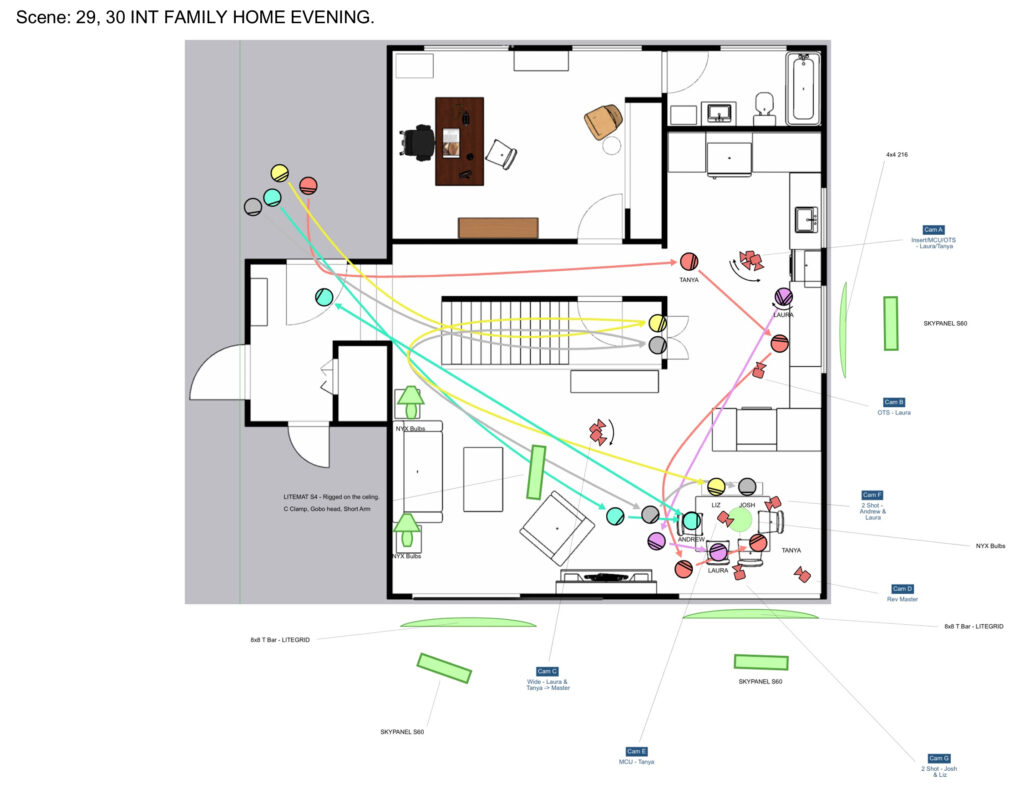

Different than a TV Movie, a feature film has more prep time for the cinematographer. They will be a part of the location scouting process, and ideally once your locations are locked you will get to spend time together at each location to shot list and diagram. Below is an example of a diagram we made for What Comes Next. Our Production Designer provided us with overhead floor plans which we imported into shot designer. Again, at this point we worked in shooting order and would pre-block the scenes in shot designer and talk through the shots we wanted to get. Then, my cinematographer- in this case the incomparable Leo Harim- would add some lighting and grip notes so that everyone knows what’s going on on-the-day.

That’s it, that’s essentially how I prep my shot lists.

There is one more thing I’d like to note for directors out there. It is about implementing your shot list when you’re finally on set. You probably noticed that I said I pre-block the scenes. This is my best guess as to how the scene will play when it goes to camera. However, I am a big fan of private blocking where the actors, the cinematographer/camera operator, and I get to work through the scene for a few minutes before we show the rest of the crew. This lets actors try things and ask questions without having to do it all in front of an audience. I always let my actors move wherever they want to the first time through. A lot of the time this will create too many position changes to be really practical and most actors will recognize this in the moment. Then we walk through it a couple more times shaping it based on the actors’ impulses and technical requirements for the shot. I have a really collaborative process and still the vast majority of scenes end up blocked very similarly to how I had originally planned. On the rare occasion that the original blocking I had in mind really isn’t working and no small tweaks will fix it, I have the bandwidth to collaborate with my cast and cinematographer/camera operator to create something that does work all because of how prepared we were going into the shoot.